How would you describe the ethos of Blackcreek Mercantile?

I would describe it as a counterpoint to a very outsourced, over technologized, complicated and disposable popular culture. It’s actually a difficult question to answer because I think that feeling is largely subjective. Some describe our aesthetic sensibility as modern/contemporary with a traditional crafted twist, some have even called it monastic. I can’t say how our work feels to other people. I can say that what I strive to evoke is a connection to bigger, more important realities. I believe that when things can be pared down to their essential elements, there can be an internal logic that comes from within which is both quiet and strong, supportive but at the same time meaningful in itself. We try to create work that is essential in this way.

Briefly, how did you come to do what you do?

I was raised to have a healthy sense of adventure along with a good dose of self-reliance. I have always been interested in design, even before I knew what that was. I studied many different subjects in school but ultimately was derailed by my love of the wood shop and building things. In many ways, I see this life as having chosen me rather than the other way around.

Tell us about the genesis of your showroom.

As our studio has grown, so have our needs and responsibilities. We have always had an open studio, so the idea was an easy extension of how we see the studio, and how we see the studio within our community. As an artist, opening the space has lead to a big boost of creative energy and collaborative potential.

How did you decide upon Kingston, New York as the site of your showroom?

Interestingly enough to me, Kingston was the first capital of New York and it is has a rich history that predates European occupation. It is also a very centrally located community to the Catskill and Mid-Hudson Valley region that has been a refuge for artists of all types since the 1800s. It is close to New York City, but not too close, urban but not a sprawl, forested, but not the wilderness.

What is the philosophy behind your craftsmanship?

>Work. We talk about what we make as work, but it is also what we do. We work to become better craftsmen; through work we gain experience and increase our skill. Through experience we gain competence and understanding. We work through designs and problems, but ultimately for me, the purpose of all the work is about connection — connection with materials, connection with process, connection with shapes, and connection with people.

What have been the biggest influences on your aesthetic and style of craftsmanship?

I can’t point to just one or two things. I am largely self-taught, so some of my biggest influences have been both trial and error. I think about design, shapes and forms like a language. I don’t think about aesthetics or style as single words but as the result of many words put together. In that, there has always been work that has “spoken” to me, forms that make sense or resonate some message. I try to see myself as a filter through which all these things pour and I see part of my job as investigating as much as possible.

I love traditional carpentry and craftwork of all sorts, Japanese, Northern European, Scandinavian, Korean ceramics, early Dutch housewares, and Shaker cast iron. I have a voracious appetite for museums and visual information of all types. I once saw a Jackson Pollock show that changed my mind about a lot of things, and I gained an entirely new appreciation for the “work” of art after reading Van Gough’s letters.

Brancusi, Noguchi, Aubock, George Nakashima, Russell Wright, Sam Maloof, Ed Moulthrop, David Ellsworth, Martin Puryear and Eduardo Chillida, just to name a few, all pioneers and giants in my mind.

You previously took a hiatus from creating furniture to focus on tabletop. Can you speak about what inspired you to return to furniture?

When we began the tabletop designs, it was in an effort to completely change pace, and to do a kind of sculptural woodwork that, I believe, was largely considered an afterthought at the time. The idea was to do something that was a different scale than furniture and at an entirely different price point, to start over from the very fundamentals to begin a new studio.

After seven years, It seemed like the time was right, the studio was ready to try some new things, able to take on more work and I had a backlog of ideas that I had wanted to try. The furniture is quite literally built on the work of the smaller sculptural items, but I wouldn’t consider them derivative. I think that the designs are able to stand on their own.

Biggest source of inspiration?

My recipe for inspiration is two to three parts perspective and one part unstructured free time.

Gaining perspective. For instance, I love being outdoors; I love the immensity of the sky, the natural order of all things and the fine, interconnected web that weaves itself out to the extremities of the imagination. For me, immersion in this kind of environment helps me gain perspective. It changes up how and where I see myself in the world. Being by the ocean is the kind of thing that, for me, demands perspective.

Unstructured free time is time to digest, which is not to say that it is passive time. I get some of my best ideas while working or doing other things – even cleaning. Unstructured, more just allowing the process to drive itself rather than pushing agendas or plans, and simply giving my subconscious the ability to do its job.

What are your bestselling pieces?

I am happy to say that most everything we have designed over the years is still in production and selling well, and the furniture we just introduced is keeping us very busy. One of my recent favorites is the cast iron door stop. The butcher blocks have also been very popular.

How has your aesthetic evolved over time?

I think I have tried to become more open and less of a perfectionist over the years, but at the same time, I sense myself gravitating to an increasingly minimal style, material rich, elemental, and evocative of process. Not necessarily by plan but on principle, this movement in my work has been steered by the mantra, “just because you can, doesn’t mean that you should”.

Can you share a bit about the process involved in creating your pieces?

With furniture- and tabletop-size work, there is no reason that the design process can’t be very interactive and hands-on. It is important for me to be able to touch the pieces and be in the same physical space as them as they are being created, not a virtual one. Some work, like turning or carving, is more or less spontaneous and is guided by feeling and process. Some work is more planned out and designed. Either way, I consider all of the work to be ultimately designed “on the saw”.

Past an initial concept, or the spark of an idea, I will usually sketch, pencil to paper, incessantly. Sketches develop into mock-ups, either 1:1 or to scale, depending on the project. Prototypes then either realize the design, are adjusted, or more are generated along the way towards producing multiples.

Where do you source your wood?

We use only domestic and sustainably sourced hardwoods. Most of the wood we use comes from the Northeast forests right here around New York, and some of the material comes from right around the block. We enjoy some of the best material of this type in the world right in our own backyard.

Describe a typical day in the studio.

We try not to have typical days.

Your studio features a few pieces by other artists, too. Can you tell us who they are and how you decided to carry their work?

The showroom features the work of other artists and designers. I think this opportunity is one of the exciting things about having a display space and the notion of curating. It doesn’t have to all be ours, everything can be different and unique, yet all work together.

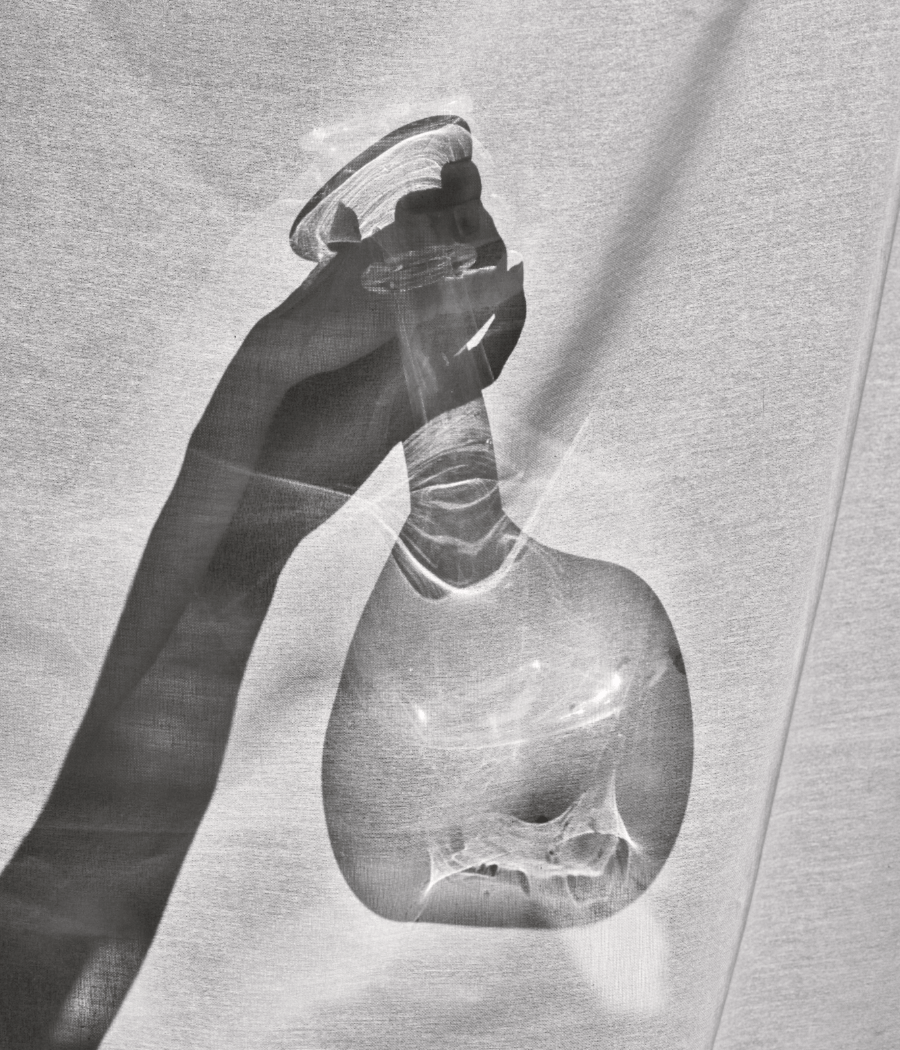

I can’t stop looking at Christopher Kurtz’s hanging wood sculpture, which I see as commanding the negative space of the room in an almost exact opposite way and counterpoint to some of my work. Robin Holland’s photographs are hypnotic meditations on the power of scale and the beauty of nature. Kathy Erteman’s bowls and vases investigate the form of hand-thrown earthenware ceramics that are colored in a beautiful but unexpected palette of earth oxide glazes. April Johnson, who is a longtime friend of mine, has a beautiful clothing line, Alasdair. I think that her work in fashion is decidedly sculptural. Ernesto Echeverria is a glass artist whose silver-leaved vases and drinking glasses border the elemental phase change between being liquid and solid. And we just started offering pants and jumpsuits by Mark Kolaski, which are very cool, stylishly casual, and workshop-tested.

A perfect Sunday is…

Spent puttering around the house.

What is your focus for the coming year?

Things are always evolving. BCMT Co. has a few new designs in the works, including a glass-topped version of our sawhorse table. We are working on a few commissions, some sculptural, some furniture, which are exciting collaborations for me. There will be more cast iron and bronze. There will be a show of turnings at March in San Francisco, and I’ll be teaching a class this summer on wooden spoon-making at the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Maine.